JOSEPH CITY, Ariz. — Brantley Baird never misses a chance to talk history, from how his great-grandmother helped settle the town of Snowflake long before Arizona was granted statehood to tales of riding to school bareback and tethering his horse outside the one-room schoolhouse.

His family worked the land and raised livestock, watching the railroad come and go and cattle empires rise and fall. Then came the coal-fired power plants, built throughout northern Arizona and northwestern New Mexico to power progress in distant Western cities.

The plants would play their own role in the history of the region and could wind up at the center of its uncertain future.

The Cholla Power Plant stands just down the road from where Baird, 88, has been building a museum to showcase covered wagons, weathered farm implements and other remnants of frontier days. For years the plant powered the local economy, providing jobs and tax revenues for the unincorporated community of Joseph City, its schools and neighboring towns, but now the vapors from its stacks have dissipated.

These days, change is in the air. Cholla is the latest in a long line of U.S. coal-fired plants to retire, shutting down in March. Arizona Public Service said it had become too costly to operate due to strict environmental regulations. The mandates were aimed at reining in coal-burning utilities, long viewed by scientists as major contributors to warming the planet.

Last month, however, President Donald Trump reversed course, signing new executive orders aimed at restoring “ beautiful, clean coal ” to the forefront of U.S. energy supplies. He urged his administration to find ways to reopen Cholla and delay the planned retirements of others. As part of his push toward energy independence, Trump has pledged to tap domestic sources — coal included — to fuel a new wave of domestic manufacturing and technology, namely innovations in artificial intelligence.

In the West, where the vision of far-off politicians sometimes crashes against reality, Baird and many of his neighbors were encouraged that Trump put Cholla in the spotlight, but there’s some skepticism about what the utilities will do with the plants.

“As many jobs as it gives people, as much help just to our school district right here that we get out of there, we’re hoping that it will come back, too,” said Baird, who used to work at the Cholla plant and has served on the Joseph City School Board.

Yet, he and others wonder if it’s too late for coal.

Just weeks before Trump announced his plans, the U.S. Energy Information Administration projected a 65% increase in retirements of coal-fired generation in 2025 compared with last year.

The largest plant on that list is the 1,800-megawatt Intermountain Power Project in Utah. It’s being replaced by a plant capable of burning natural gas and hydrogen.

Utilities, already looking to increase capacity, aren’t sure Trump’s orders will lead them back to coal.

“I think it’s safe to say that those plants that are scheduled or slated to retire are probably still going to move in that direction, for a couple of reasons,” said Todd Snitchler, CEO of the Electric Power Supply Association, which represents power plant owners. “One of which is it’s very difficult to plan multimillion- or billion-dollar investments for environmental retrofits and other things on an executive order versus a legislative approach.”

Last month, Republicans in the Arizona Legislature sent a letter to U.S. Interior Secretary Doug Burgum warning that the economic fallout from the 2019 closure of the Navajo Generating Station is still reverberating. The stacks were demolished, and the mine that supplied the plant closed.

At the San Juan Generating Station in northwestern New Mexico, operations ended in 2022.

Stuck in the middle are Joseph City and other communities where life revolves around a power plant. Residents hope Trump can help keep them in the energy race for another generation. From Joseph City to Springerville, they’ve been preparing to absorb major hits to the job market, tax rolls and school enrollment. Options are slim in Apache and Navajo counties — two of Arizona’s poorest.

Utility executives told Arizona regulators recently that reopening Cholla would be costly for customers and that they plan to push ahead with renewable energy. The plant’s infrastructure would be preserved as a possible site for future nuclear or gas-fired power generation, and the Springerville Generating Station could be repurposed once the last units are retired in 2032.

The utility that runs the coal-fired Coronado Generating Station, just 30 miles (48 kilometers) away in St. Johns, also has plans to convert to natural gas.

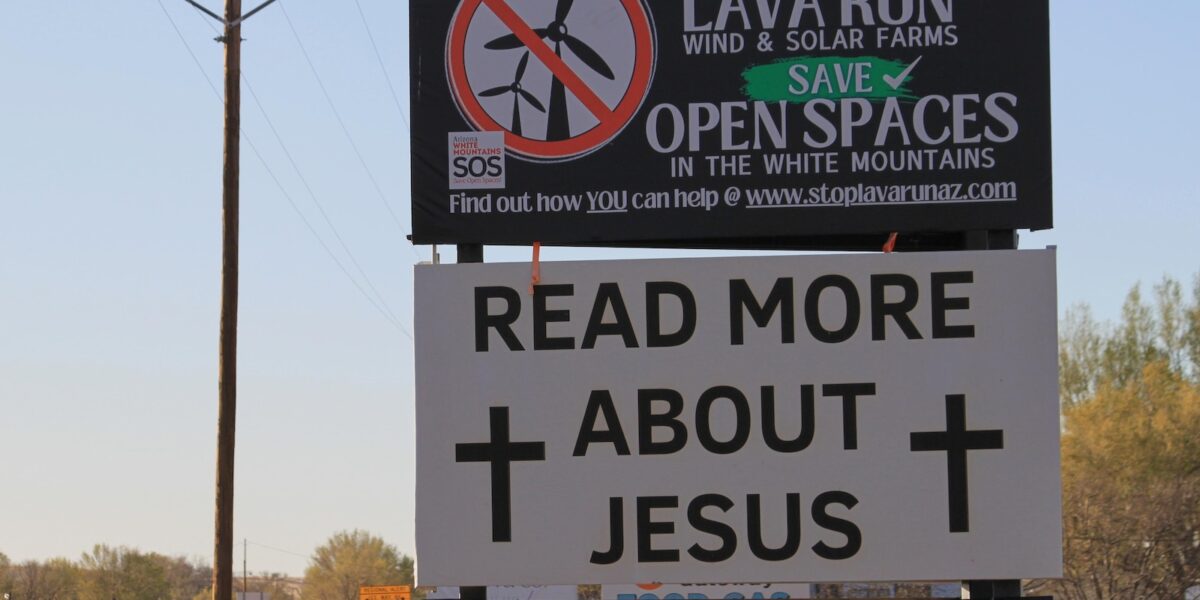

In Springerville, the idea of spoiling the surrounding grasslands and ancient volcanic fields with 112 wind turbines — with blades standing taller than Seattle’s Space Needle — provokes outrage. Banners and posters objecting to the proposal are plastered around town.

“They all know that this won’t work, that we can’t rely on wind and solar,” said Doug Henderson, a Springerville plant retiree who now sits on the town council. He says coal-fired generation can accommodate swings in demand, regardless of whether there’s sunshine or wind.

Springerville Mayor Shelly Reidhead and others are fighting to keep the wind farm from happening, saying repurposing the Springerville coal plant would mean more jobs and preserve the surrounding landscape.

“We also survive on tourism and people don’t want to come here and look at that,” Reidhead said of the turbines.

The Western Drug and General Store is adorned with tiny American flags tacked up outside. A sign advertises canning supplies, but locals joke that you can get anything here — from slippers to rifles.

Andrea Hobson works the register and knows everyone by name. She moved to Springerville about 20 years ago from California and says it’s hard to imagine the community without the power plant.

“It would be a ghost town. It really would,” she said. “That’s the heart of this town.”

Springerville’s leaders have lost sleep trying to figure out what industries might fill the void. At stake are about 350 jobs, dozens of contract employees and the businesses they support — from the general store and the new frozen yogurt shop to the hospital and local churches.

Some workers drive an hour to the Springerville plant every day, meaning other communities also will lose out, said Randel Penrod, a former crew manager at the plant. With retirement looming, the plant has trimmed its workforce.

Henderson, the Springerville town council member, fears it could take years to permit a new plant.

Reidhead is more hopeful after attending meetings with members of Arizona’s congressional delegation and utility executives. She thinks the Trump administration can reduce the “red tape” and get new plants up and running. The development of artificial intelligence and its thirst for power gives the mission a sense of urgency.

“I think our politicians at a state level have realized with AI’s need for the power, that if we don’t get on board and get on board soon we’re going to be left behind,” she said.

Some energy analysts say Trump’s support of coal is mostly symbolic, since utilities hold the keys. Others say diversifying energy sources is a must as the U.S. sees increases in power demand predicted for the first time in decades.

“AI may be artificial, but the electricity it needs is very real — and in some regions, coal still keeps the lights on when other sources may blink,” said Scott Segal, a partner with the Washington D.C.-based firm Bracewell LLP.

He said power markets don’t care about politics — just reliability, affordability and sustainability.

Just outside of Joseph City, crews are building what will be one of the largest solar and battery storage projects in Arizona. The solar panels will be installed on leased private land, including Baird’s sprawling ranch.

While not a fan of all the dust being kicked up, Baird knows the advent of solar is just another of many changes he has seen in his lifetime — and he has no idea what the next 100 years might look like.

“Hell, who knows?” he said. “You know, when it comes right down to it, we’ll just wait and see.”

___

Associated Press writer Marc Levy in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, contributed to this report.